Six Ways Acquirers Value your Company

The value of your company depends on what motivates your acquirer.

This piece was originally published on The Founder Coach. Dave Bailey coaches tech CEOs from Series A to pre-IPO. Find out more about his coaching programs and podcast.

There’s a lot of PR attached to $100M+ acquisitions, which makes them seem more common than they actually are. In reality, only a small fraction of companies ever get acquired, and of those, very few are valued in hundreds of millions of dollars.

For those of you building companies — or working at a company that may one day be sold — here’s a run-through of the six levels that motivate acquirers to buy companies, and the methods they use to value them.

Level 1: Talent acquisition (recruiting fees + time advantage)

Even if your product hasn’t hit the market yet, your company may have some value. Companies that need to scale quickly often buy small companies to speed up their growth, and this is called an ‘acquihire’.

Acquihires are popular when the market for talent is fiercely competitive. However, not all talent is created equal. Usually, acquirers care most about technical talent, i.e., machine learning programmers, AI specialists, and PhDs in data science. The unit of value in an acquihire is thus typically ‘per engineer’.

The acquisition process frequently involves multiple interviews with every team member — and if they don’t pass the interview, the deal can fall through.

Level 2: Filling a product gap (replacement value + time advantage)

Let’s say you have the team and a product in the market — but the product isn’t growing fast enough. However, your product works and even integrates with a few third-party services . . . and for the right acquirer, this is valuable.

In a scenario like this, an acquirer may run a ‘build vs. buy’ analysis to understand how much it would cost, in terms of time, resources, and opportunity, to staff a team and rebuild a similar product themselves. When it comes to tech, time is usually of the essence, so this can be a real advantage.

Level 3: Driving revenue (the ‘DCF’ model)

You have the team, a product in the market, and you’re actually making money. Congratulations — now you have even more to offer, since your revenues can become an acquirer’s revenues.

When acquirers evaluate a company with revenues, a popular approach is to forecast future cash flows and use complicated formulas to buy those cash flows at a discount — hence the name: the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model.

When revenues are uncertain, it’s common for acquirers to negotiate an ‘earn out’ clause — a financial incentive to stick around and maintain good performance after the acquisition.

Level 4: Addressing a strategic threat (customer acquisition costs)

Your market share is growing, and someone sees you as a threat — or as an opportunity, since the two are intimately linked. They might acquire you to get closer to market dominance.

There are many reasons for this scenario arising, but it commonly happens when both companies are targeting the same set of customers. Aside from acquiring your product capabilities and cash flows, they can also cross-sell to your customers (and vice-versa).

Level 5: Entering a new market (EBITDA multiple)

You’re one of the leaders in your market and you’re attracting attention. Rather than enter a new market from scratch, acquirers often prefer to buy a company that’s already doing well.

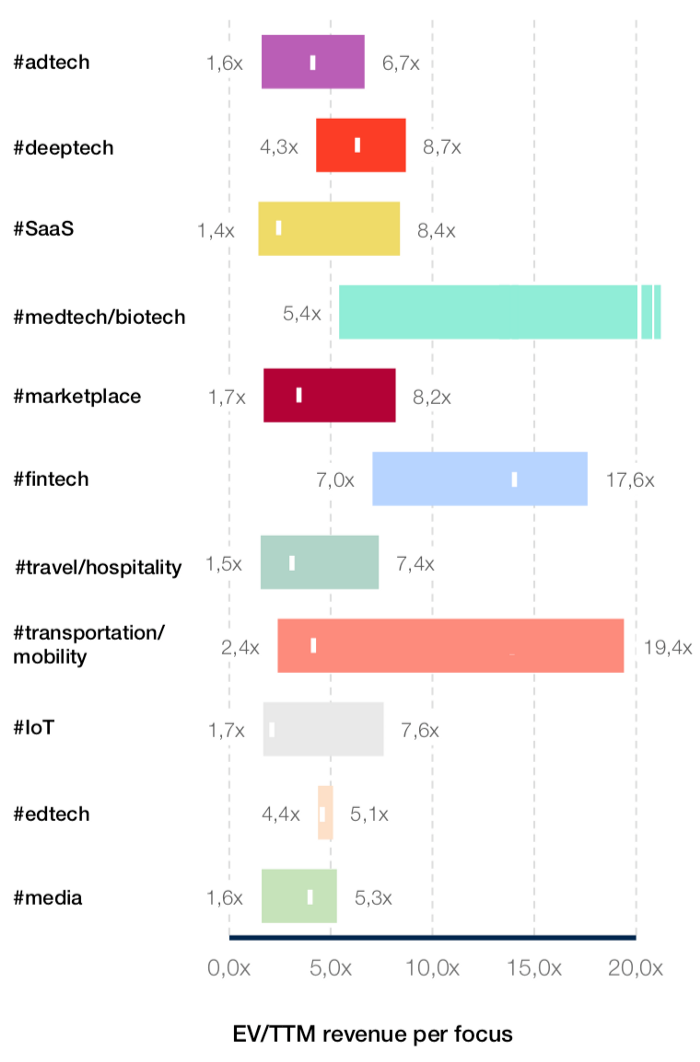

At this stage, you can often infer the value of your company by comparing it to other companies in the market, based on either revenue or profits of the trailing twelve months (TTM). Here’s what European revenue multiples look like in some common tech markets:

Level 6: Defensive move (the wildcard)

When you see a valuation so outrageously high that makes you wonder if an acquirer’s calculator is broken, it’s probably some form of self-defence.

If a company’s leaders believe you’re on track to disrupt their product or give their competitor a unique advantage, they may pull out the stops to buy you, just so others can’t.

At the time, Facebook’s eye-watering purchase of Instagram looked beyond extravagant — but now it looks like a bargain.

So, you have some interest...now what?

If you’re creating a lot of value very quickly, it might be too early to sell. Instead, you might respond by saying, ‘We’re open to forming partnerships that help us scale faster.’

But if you’re interested in selling, the next step may be to get board approval to run a formal process — after all, you have a fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of all shareholders.

‘What’s a formal process?’ I hear you ask. Well, it means you reach out and hold parallel conversations with multiple potential acquirers. These may include direct and indirect competitors, suppliers, integrations, and existing partnerships.

Depending on your stage, your value may not be obvious — and that’s why a common approach is to ‘explore partnership opportunities’. Exploring partnership opportunities is a bit like dating — sure, you’d both like to get married one day, but you want to find out if you’ll even hit it off first.

Once you understand potential acquirers’ issues and fears, you can identify ways to help them. And if you can form a partnership with senior buy-in, then any news of a possible acquisition is likely to trigger an emotional reaction — nobody wants to lose something they thought they already had.

To add fuel to the emotional fire, many companies invest in PR to get their company’s profile in the press and create hype. This is where your choice of investor, board member, banker, and lawyer can also have a material impact on your credibility.

In a typical process and with a lot of work, you may reach out to twenty companies, sign between five and eight NDAs, and get two or three bids.

Acquisition — everyone’s Plan B

Getting acquired may one day provide you with an option to exit your business and capture some of its enterprise value, whether that’s in cash or stocks in the acquirer’s company.

And for the many who take on venture capital and find themselves unable to raise another round, acquisition may become the most viable option to keep the company alive.

Depending on your last valuation, even a modest return to your investors of 1.5X can be significant for you as the founder — and in the end, not every founder wants to run a public company.

Further reading: How to Set Up Your Company for Acquisition

This piece was originally published on The Founder Coach. Dave Bailey coaches tech CEOs from Series A to pre-IPO. Find out more about his coaching programs and podcast.